If you’re running CPI campaigns as part of your mobile app advertising strategy, Return on Ad Spend (ROAS) is probably one of your go-to metrics. But it might not always be the most reliable indicator – especially if you fall victim to organic poaching.

To realize optimal outcomes from CPI campaigns, buyers need to be sure that the channels in which they’re investing are delivering true performance. The effectiveness of these channels is usually tracked with a Return on Ad Spend (ROAS) calculation – but what if paid channels aren’t delivering the return they appear to be?

Every application has some organic, intent-driven installs and it is this type that is vulnerable to organic poaching. This form of advertising install fraud can make paid advertising-based install channels appear far more performant than they truly are and result in wasted budget and deceptive incrementality statistics. Importantly, organic poaching isn’t just incrementality by another name – it’s a targeted action with the goal of stealing credit for app installs.

With the scene set, let’s look more closely at organic poaching, how it can obscure the reality of your ROAS calculation, and what to do about it.

What is organic poaching?

Organic poaching is a form of mobile ad fraud in which a specific advertising channel takes credit for an app install which would have taken place anyway.

All apps have a certain level of organic appeal – due to good reviews, quality app store optimization, positive word-of-mouth, and so on – which means some installs will always happen naturally. Because of the natural intent of these organic users – i.e. they genuinely want to use the app – they usually deliver a much higher Lifetime Value (LTV). By contrast, users delivered via other channels (including fraudulent ones) may not provide quality LTV. It makes sense, then, that fraudsters would prefer to take credit for organic installs, even though their channel didn’t actually generate the install in the first place.

Similarly, buyers working on the basis of strong ROAS performance are likely to funnel more budget towards these channels because they appear to be highly performant. But there are telltale signs of organic poaching, especially as it relates to ROAS, which we’ll look at in more detail in the next section.

Like the wider programmatic ecosystem, mobile app advertising traffic must pass through a supply chain in order for installs to be measured and attributed. It’s as this traffic passes from an app publisher to an ad network to an MMP (Mobile Measurement Partner) that organic poaching can take place.

The mechanics of organic poaching

The mechanics of organic poaching differ, but all methodologies involve some form of fraudulent click attribution whereby the MMP accredits an organic install to a paid channel.

As mentioned above, organic poaching is entirely separate from incrementality, which can often have a fuzzy definition. While incrementality is a measure of performance lift based on a specific action (e.g. the showing of an app install ad), organic poaching is a targeted and specific act of fraud which aims to obscure or alter install statistics to make a specific channel appear more performant than it really is.

There are several different ways that advertising channels can carry out organic poaching, but here are the most common:

- Click or impression spamming refers to the buying of cheap inventory with no associated user intent with clicks or impressions artificially generated on behalf of a user via pop-ups or other nefarious tools.

- Fingerprinting refers to the buying of clicks or installs which have no device ID (IDFA, MAID) associated with them. Taking advantage of the lack of these IDs, the organic poacher will generate many installs from the same device.

- Click injection is perhaps the purest form of ad fraud under the umbrella of organic poaching. With click injection, an attacker can hijack a specific genuine app install signal to claim credit for an install of a different app.

The truth about ROAS in CPI campaigns

ROAS is naturally only calculated against paid channels, but with organic installs boasting a much higher LTV, it’s easy to see why they’re so appealing to fraudsters.

For this reason, ROAS can be a good indicator of when organic poaching is taking place.

Let’s look at an example.

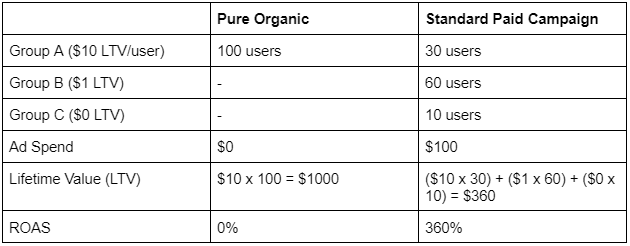

Imagine you have three groups of users:

- Group A are highly relevant users with strong intent who like your app and want to install it. Lifetime value (LTV) for these users is $10.

- Group B are paid users who were incentivized to install your app through a rewarded or incentivized creative. Intent is generally low. LTV for these users is $1.

- Group C is app install fraud. Intent here is zero. Lifetime value for these users is $0.

Let’s take these groups and look at an example ROAS calculation. It makes sense that you would capture some of the organic group A in your CPI campaigns, so we’ll include those in our example below.

In this example, a channel delivering users like Group C – generating absolutely zero incremental installs – has almost no reason to exist on a media plan. But, to the unscrupulous ad network behind this paid channel, they may want to make it appear as though it is performing by reporting fraudulent clicks to the MMP.

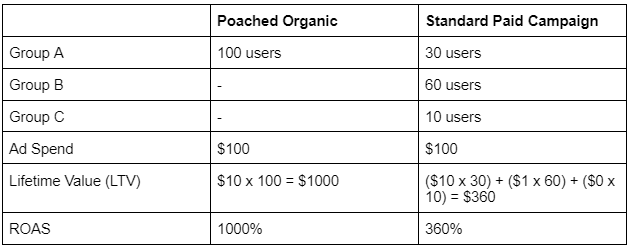

Now let’s assume that this ad network has decided to deploy organic poaching to take credit for the entirety of group A. Here’s what that would look like in terms of ROAS:

With the ROAS calculation now being applied against the $10 LTV of the organic group A, suddenly performance is looking much more impressive.

For a media buyer who is unaware of organic poaching, this ROAS will be a compelling reason to funnel even more budget towards this paid channel – but this is the wrong move.

How to solve organic poaching

It’s clear that organic poaching is a problem, so how do you go about accounting for it? How can you spot organic poaching within your CPI campaigns? And how can you use this information to choose incremental partners that actually deliver?

One of the biggest hints that organic poaching is taking place is that overall growth of installs is not going up over time. This is because you’re essentially paying for an audience which is already yours. The proportion of your paid spend may increase as you funnel budget towards poached channels, but the overall number of installs will not – or at least not significantly.

To test this theory, you could turn off specific mobile ad networks and assess the result on total install numbers. If they stay roughly the same, there’s a high likelihood that this ad network was poaching installs.

In addition, it’s a good idea to monitor your organic install numbers closely. If these go up (or down) as a proportion of total installs when making changes to your paid channels, it could be a clue about some potentially questionable activity with your ad networks.

Finally, you could also compare install delay curves. We’ll go into more detail on delay curves in another article, but the high-level summary is that you can use the time it takes from ad click to app install to judge incrementality across advertising partners. Unlike direct incrementality measurements, which require complex frameworks, long test periods with audience splits etc, install delay curves – or even just the percentage of installs within the 1st hour of an impression – is something everyone can calculate based on MMP log numbers or metrics.

While this method doesn’t speak to pure financial performance like ROAS does, it doesn’t carry the same risks of organic poaching and can therefore be a good metric to at least consider when reviewing incrementality in CPI campaigns.

If you’re looking to amplify your mobile advertising campaigns and unlock maximum ROAS, get in touch with the IPONWEB team today.